Geeby Dajani: Leader of the Latchkey Kids

The life and times of a Palestinian punk-rocker-turned-hip-hopper in New York City

The following was originally published in Palestine in America’s 2020 Music Edition. Order a print copy or download a digital copy today!

One hot summer night on the west side of Manhattan in the early 1980s, on the roof of the boisterous, four-story nightclub called Danceteria, a group of teenage friends stood in a cypher writing rhymes on a notepad. They were an irreverent crew of rascals, the children of Manhattan artists — an aspiring painter, Cey Adams; an aspiring guitarist, Adam Horovitz; and an aspiring actor, Nadia Dajani, along with their friends Dave Scilken and Adam Yauch, who had traveled all the way from Brooklyn to join — skilled in the ways of talking (or sneaking) themselves into clubs that they certainly weren’t old enough to be in. As they basked in the smoke of cigarettes and the club’s (probably illegal) barbecue grill, another crew caught Dajani’s eye from across the rooftop. She stepped away from the cypher to get a closer look. Under the light of the moon and the rooftop’s neon signage, their faces came into focus: Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, and Madonna.

“They were at the top of their game, and they were all so famous,” Dajani says. “And I looked back at my friends and thought, ‘Well, I wanna be an actor, Cey is a graffiti artist, and Adam Horovitz and Adam Yauch wanna be musicians; I wonder if one day we’ll be them, and some young kid will be looking at us.’”

It’s a Dajani sense of ambition that runs centuries deep.

The Dajani family is one of the most storied families from Palestinian Jerusalem, originating from a village just outside of Jerusalem called Dajaniya. It’s believed that the Dajani family are direct descendants of the Prophet Muhammad (Peace be upon him.) The first to carry the family name was Sheikh Ahmad bin Ali, who, according to the oral tradition, came to the village in the 16th century after leading a diverse caravan from Fez, Morocco, through Jerusalem, and on to Mecca. Sheikh Ahmad presided over a dispute between two families in the village and ruled in favor of the weaker, poorer family. After the stronger family made hostile threats toward him, he sought to leave as he felt he was no longer welcome. Despite the village leader’s best efforts to persuade him to stay, Sheikh Ahmad had made up his mind. In response, the leader requested that he carry the village name with him on his travels, so that all whom he met would associate him and his righteous ways with the village. He then became known as Sheikh Ahmad Al-Dajani.

Centuries later, in a different time and place, Sheikh Ahmad’s descendant and Nadia’s brother, Najeeb “Geeby” Dajani, would leave an enduring impact on New York City’s punk and hip-hop scenes.

By the middle of the 1960s, the Dajani siblings had all arrived on Earth. They were born to a Palestinian father and an Irish American mother — Magda, the eldest, born in America; twin brothers Najeeb and Tarek, born in Cairo; and Nadia, the youngest, also born in the States. In 1968, when the twins were seven, the siblings moved with their mother to New York City and eventually into the Westbeth Artists Housing community, located in Manhattan’s West Village. Over a century old, and originally the home of Bell Laboratories, it was reopened as an affordable housing complex for artists in 1970. Jazz legend Gil Evans lived there and entertained guests like his friend Miles Davis; Keith Haring’s first art exhibit took place at Westbeth in 1981; Vin Diesel grew up there; and seemingly all the important relationships in the Dajani siblings’ lives took root in its halls and on the surrounding streets.

One of Nadia’s first meaningful bonds was formed in the family’s Westbeth apartment, and it was Najeeb (known as “Geeby”) who was responsible. Nadia, soft “a,” and Geeby, hard “G.”

“I had real bad separation anxiety when I was a kid,” Dajani remembers. “My mother would say goodnight, and I would be trying not to cry, when Geeby would crawl into my bed and put a transistor radio between our heads, and I would fall asleep to Phil Rizzuto calling Yankees games.”

Linus had his blanket, and Geeby gave Nadia her New York Yankees.

“We would hop the D train,” Dajani reminisces. “[We’d] buy a ticket for a buck fifty, sit in the bleachers, and then do our homework on the train coming back, and be home by dinner.”

“I remember [her] bedroom was plastered with Yankees posters,” Horovitz recalls with a laugh. “Everywhere was just baseball and the f---ing Yankees.”

The Horovitz family are New York Mets fans, you see, and baseball is serious in New York.

But as much as baseball was a wedge between the two families, it was also a bridge. It was on the Greenwich PS 41 Elementary School playground that Geeby Dajani’s love carried over. He taught Nadia Dajani how to throw a curveball and gave Horovitz his first baseball glove.

“[PS 41] had a big schoolyard, so, after school and on weekends, everyone would just go hang out at the schoolyard,” Horovitz explains. “The younger kids, me and Nadia, would get pushed to the side by all the older kids. A lot of ‘em were in this thing called the GO Club, which was a downtown gang.”

“It started out as a graffiti club,” remembers Geeby’s best friend, Nelson “Keene” Carse, who met him in second grade. “There was all these different graffiti crews from uptown and downtown, but the GO Club [started with] me and maybe five or six guys.”

“They were some wild f---ing kids,” says Horovitz.

When they tagged (or signed their graffiti), Keene was known as “TEAM,” and Geeby was known as “ME62.”

“I was more into it than Geeby was,” says Keene. “It was my whole life for a while.”

The Clash’s “Tommy Gun” may be the first song in Western music to make lyrical reference to Palestine.

Still, in 1979, the year after Joe Strummer first sang “…standing there in Palestine lighting the fuse…” on The Clash’s “Tommy Gun,” it was Geeby’s graffiti that would be forever immortalized. Geeby’s ME62 got extended screen time alongside his Westbeth neighbor John Gamble’s RATE5 in a subway scene from the film “The Warriors.” It would be a running theme in his life: Geeby having a lasting impact on things he was just trying out. Usually, they were things he was trying out simply to support his friends.

“[Their tags] were all on the trains,” remembers Horovitz. “So when you would take the trains to school you would see their names up there. It was amazing.”

So, you see, it wasn’t just any older kid giving Horovitz a baseball glove. It was ME62, a budding neighborhood superhero writing his own origin story. It was Geeby Dajani, who could have been the inspiration for Benny Rodriguez in “The Sandlot.”

“When the cool older kid gives you something,” Horovitz says, “You think, ‘Woah, what does that mean about me?’”

Horovitz had been anointed by Geeby, and so Horovitz was destined to write his own legend, too.

Within the walls of the Source Academy, a very small, private high school on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Geeby Dajani was a stellar hockey player known for using his tall, muscular frame to his advantage.

“I honestly thought Geeby was Puerto Rican at first,” laughs childhood friend, and Geeby’s future creative partner, Dante Ross. “I had no idea he was Palestinian. I met him playing hockey in the basement of Westbeth — maybe I was twelve — and he completely bodied me. He checked me through a wall. A day or two later we were at school, and I was like, ‘Yo, what the hell was up with the Puerto Rican kid?’ And Nadia was like, ‘My brother’s not Puerto Rican!’”

There were several main extracurricular activities by this point: in the summer they played stoop ball or baseball if they had enough people; in the winter they played hockey and had snowball fights; and no matter the season, when the sun went down, it was nightclubbing as Grace Jones once sang. The clubs were where you met new people, learned new dances, and got into new trouble. The thing was, Nadia and Horovitz didn’t have money for cab rides, cover charges, and drinks, so they would rally a baseball lineup’s worth of friends, pile into a taxi, split the fare, and head to a club called Palladium on 14th Street.

“Geeby and a bunch of his friends were barbacks there,” says Nadia. “At a certain time, he would say, ‘Be outside this door on 14th Street.’ Me and my friends would be there, and Geeby would come and open the door and let us all in the back door. We’d hustle our way up into the VIP room, and people like Jean-Michel Basquiat would be there every single night of the week because that’s what everyone did.”

Then punk hit. It was loud, it was fast, and it wasn’t on ice. Punk was perfect for being a teenager in New York City.

“You gotta remember,” Ross explains, “We were all really crazy, aggressive f---ing kids. New York was in a steep, steep decline as a city, and it was relatively lawless. Going to hardcore shows was a really cathartic way for all of us to channel our aggression.”

“We were all latchkey kids,” says Nadia. “We basically just had to be home for dinner.”

“I started getting into punk after my brother and sister had played me The Clash,” remembers Horovitz. “Then I started going to punk shows and went to Irving Plaza to see a Misfits show, and there was Geeby stage diving. And I was like, ‘Woah, this guy, what is he doing here?’ It was not what I ever would have thought he’d have been into.”

If you were a teenager in the late ‘70s or early ‘80s, the music you liked informed the way you dressed, so what you wore was your chance to announce yourself to the world. Geeby didn’t dress like someone you’d expect to see at a punk show. Punk’s do-it-yourself aesthetic was a natural draw for a bunch of kids of artists who could maybe afford to split one drink together at the shows they’d snuck into. If you were into ska, maybe you dressed like a 2 Tone; if you were into any band that had ever made a “rock opera,” you dressed like a mod; if you were into disco, you probably wore disco pants and took disco naps; and if you were into punk you were either a hardcore kid with short hair, a mohawk kid, a dreadlocks kid, or a skinhead. In any case, there was a good chance two things were certain: You were wearing boots, and you got your threads from Trash & Broadville. Partly for lack of money, partly because of his personality, Dajani never sartorially identified with any of the music fashion tribes — and yet he was the skipper of the squad.

“He was the leader of the Westbeth guys,” Ross recalls. “He was the Minister of Chaos in that crew. I particularly remember one drunk night Geeby inspired us to steal the Trash & Broadville sign off of the front of the building, and we did. We literally pulled it off of the building itself, walked like three or four blocks, and destroyed it.”

In 1979, Geeby left for college in Arizona; he didn’t last long there and was back in New York by 1981. When he returned, he found that a group of Westbeth kids had started a hardcore punk band called Frontline.

At the time, Gamble sang for Frontline and was backed by guitarist Miles Kelly, Mackie Jayson on drums, and Noah Evans (son of Gil) on bass. They, too, were known by their graffiti tags: Kelly was “RAGE,” Jayson was “HYPER,” and Evans was “NOAH.”

“Frontline were like a combination of The early Who and Motorhead,” says Horovitz. “And faster.”

An early Frontline recording featuring Kenny Liburd on vocals.

Geeby’s best friend Keene had formed a ska band called Urban Blight, Horovitz had started a hardcore band called The Young & The Useless, and Yauch had joined another hardcore band called the Beastie Boys. Geeby didn’t have a band, though, or at least not at first. In the beginning, he was perfectly happy just showing up to dive into the mosh pit at his friends’ shows.

At a hardcore show, everyone finds their place; some play the wall, some skank around the perimeter of the mosh pit, some dance their way right into the pit’s swirling vortex of colliding bodies. Others, those with ambition and reckless abandon, take a running start from the stage and dive directly into the center of the maelstrom. They’re known as stage divers or stage jumpers, and Geeby, who now stood 6’2” and weighed in the neighborhood of 185 pounds, was one of the best. Heroes are either made or dethroned in the brief moments that they hang in the air above the moshing crowd.

“I tried it once, and all the dudes moved out of the way,” Keene painfully remembers.. “I hit the floor, and they all started kicking me so I was like, ‘Alright, I’m not gonna try that again.’”

The pit was already a violent place, and if he wanted to make it out alive, Geeby had to put his hockey skills to good use.

“He was a master at stage diving and taking out rows of skinheads, or eggheads, as we called them,” says Ross. “It was almost a contest to see who could take out the most people with a dive, and he definitely had the most.”

“When we’d go to shows at CBGB’s,” explains Keene. “He’d be on the side of the stage and turn to me and say, ‘Watch this, Keene.’ He’d go up and run and jump off the stage and dive into the crowd and take a bunch of people out. [Then] he’d come slithering through the crowd back to me, laughing. It was so funny to watch. He loved it. It was a sport for him.”

By this time, Horovitz was finally old enough to try to hold court with Geeby and his friends.

“I started hanging out with Geeby and the Westbeth people a little bit more, specifically, Miles Kelly and the guys from Frontline,” Horovitz remembers.

Horovitz’s The Young & The Useless — and another called the Beastie Boys — started to play shows at the same venues as Frontline, eventually sharing the same bill.

Over time, punk’s beats per minute got faster; the change in tempo from The Clash, to the Ramones, to The Misfits, to bands like Frontline was dramatic. Then the Bad Brains happened. The all-Black Bad Brains were an explosive hardcore band from Washington, D.C., who left an unremovable stain on punk culture and whose shows were a place that punks of different kinds called home.

“Bad Brains was something different,” says Horovitz. “They had a different feeling, and it must have touched [Frontline]. Every Bad Brains show I would see those guys there.”

Nadia remembers it the exact same way.

“If you found out the Bad Brains were playing,” she says, “You dropped whatever you were doing and had to figure out a way to get into the show.”

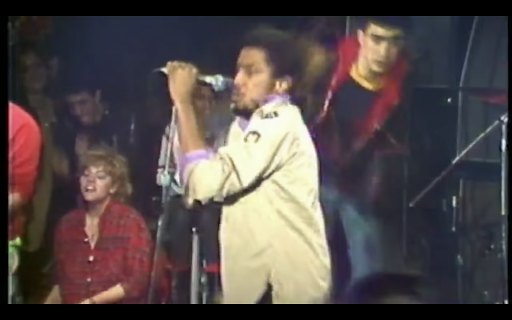

By the early ‘80s, Geeby’s growing legend and the proximity of the Westbeth space, helped him form a friendship with the Bad Brains. In fact, Geeby is one of the first stage jumpers visible in the Bad Brains’ Christmas 1982 concert at CBGB.

This recording of the Bad Brains Christmas 1982 show at CBGB’s is considered among some to be the most important documentation of hardcore.

While lead singer H.R. is stomping a hole in center stage, Geeby winds up for a majestic jump. Beginning behind the stage near bassist Darryl Jenifer, Geeby pushes off to gain quick momentum, takes a few powerful steps, and flies off screen.

“Having Geeby there behind me was almost like protection in a way,” recalls Jenifer, fondly. “But not like security; security are some dudes you pay to guard you. Geeby was my brother, you understand? So if I’m in the midst of the rock and the roll and dudes are wildin’, dudes wanna jump on stage, maybe they wanna try to pull the plug outta my bass and all that shit, Geeby would be lookin’ out watching my s---. So when I look to my side, I’d see Geeby, I’d see [other friends like] Harley, I’d see maybe Miles, and then I feel that I’m protected.”

The running stage jump lasts about three seconds, but in that time one can learn so much about Geeby — the stoic poise in his eyes amidst the chaos, the confidence and leadership it takes to be one of the first. In school, there are those of us who volunteer to read and those of us who keep our heads down hoping we won’t get picked; Geeby was the former — assuming he wasn’t skipping class. Only a few seconds after his stage jump, just as Keene had described, Geeby slithers back to take his spot behind Jenifer. To jump in and out of a whirling mosh pit says a great deal about a person — not just their physical strength, but also the coordination, control, and confidence they possess.

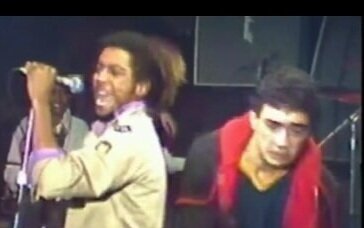

In 1983, the year after Geeby’s immortalized Bad Brains stage dive, Frontline found themselves without a lead singer. So, they turned to Geeby. It wasn’t so uncommon for people to join a band in this manner; after all, it was Horovitz who showed up to a Beastie Boys show one night and filled in for their missing guitarist. The rest is literally history.

For Geeby, the convenient thing about singing in a hardcore band was that he didn’t need to be technically good at it.

“If you’re a technically good singer, you’re a bad hardcore singer,” Ross says.

Geeby stayed true to himself during his stint as the band’s lead singer. He had the self-awareness to know that he wasn’t who you’d expect to see fronting a hardcore band, so he poked fun at himself. On one particular rainy night, Frontline played at CBGB’s, and someone in the front row was eating a sandwich. In the middle of a hardcore show, just eating a sandwich. So, naturally, Geeby grabbed an umbrella that was laying near the stage and used its pointy end to skewer the sandwich before taking a bite, kebab style.

“The thing about him singing in Frontline is that he spent more time diving into the audience and taking dudes out than he did on stage,” Ross recalls fondly. “I think they made him the singer because he was just mad cool. ,” Ross saytheorizes. “They were just like, ‘Oh, let’s make the coolest and toughest guy in the crew our lead singer.’ He was by far the toughest guy of all of us growing up.”

A young Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz of the Beastie Boys stage jumps at a Frontline show in 1982. (Photo courtesy of Freddy Alva, from his photobook “Urban Styles: Graffiti in New York Hardcore.” Available at wardance.bigcartel.com)

“Again,” emphasizes Horovitz says, “It was furthering [Geeby’s mystique.] Like, ‘He’s the singer for a hardcore band now?’”

Geeby’s stint with Frontline lasted 10 gigs, but in that time he managed to write and record a tape of songs with the band. The Frontline demo made its way from Miles Kelly’s hands into the pocket of Yauch, where it stayed for years. In the meantime, Geeby’s friendship with the Bad Brains progressed to the point that they invited him on the road.

“Gee was friends with the Bad Brains through a cat named Dave Hahn,” says Chip Love, Geeby’s friend. “He was their manager early on and got Frontline a lot of gigs opening up for the Brains. They became friends, and the Bad Brains took Geeby on the road with them [as well as] myself and a bunch of other friends who turned into ‘roadies.’”

Geeby joined the tour as a close friend, occasional fitness instructor, and, more professionally, as the band’s drum tech.

Of course, Geeby took his acclaimed stage jumping antics on the road, too.

“If we were watching someone else’s show,” Jenifer says through a laugh. “Geeby would say, ‘Yo, Darryl, hold my s---.’ And I would say, ‘Uh oh, my man’s goin’ in!’”

Despite all prior Geeby-inspired moments of amazement in his life, Horovitz was still surprised when the Beastie Boys ran into him on the road with Bad Brains.

“I think we ran into them in New Orleans,” says Horovitz. “It was like, again, ‘Woah! What is f---ing Geeby doing here?’”

“I got locked up that night!” exclaims Jenifer. “So me and Geeby, we up in the bar, and then we went outside, and I had my beer, but I figured it’s Mardi Gras, so it’s no problem. But I was from outta town, so I didn’t know you couldn’t have no bottles. These cops rolled up while I was outside talking to Geeby and said, ‘Yo! Get your a-- back in that bar with that brew.’ But I looked at ‘em and just went back talkin’ to Geeby. I did it on purpose! I’ll never forget. Like, ‘So, whatever Geeby, anyway like I was sayin’...’”

Geeby wisely suggested they move back inside the bar, but by then the damage was done. The cops had already set their sights on the Black and brown dudes standing outside, and Jenifer’s cool indifference was the final straw.

“Next thing I heard was the cop doors closing, and they came in, and I started saying, ‘Nah, nah, Mr. Officer,’ and all this shit. That’s when it was my turn to say, ‘Yo, Gee, hold my coat.’”

In 1987, while Geeby was on the road with Bad Brains, the First Intifada (or uprising) in Palestine broke out. Palestinians, frustrated by two decades of the Israeli military’s occupation of Palestinian land, began large-scale protests that sustained for over five years. It’s maybe no coincidence that graffiti was an integral part of the Intifada, connecting Geeby spiritually with his ancestors’ homeland.

“It’s my guestimate that around the time of the uprising is when it became a point of pride [for me and Geeby] to be called Palestinian,” remembers Nadia.

A decade later, at the 1998 MTV Video Music Awards, Yauch spoke out against anti-Arab racism and Islamophobia. After Public Enemy’s Chuck D presented the Beastie Boys with the Video Vanguard award, Yauch spoke his mind.

“America really needs to think about the racism that comes from the United States towards Muslim people and towards Arabic people,” said Yauch. “That’s something that has to stop. The United States has to start respecting people from the Middle East.”

Adam “MCA” Yauch of the Beastie Boys speaking out against Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism at the 1998 MTV VMA awards.

Seeing their childhood friend use his platform to stick up for them was a source of pride for Geeby and Nadia.

“After Yauch gave that speech, Geeby and I gave each other a little fistbump,” Nadia says.

[Editor’s Note: As a young Arab kid, this was the first time I could remember feeling seen by any kind of pop culture figure.]

After 9/11, Yauch would use his voice to once again take a stand for Arabs. When Yauch told MTV News he has friends of Middle Eastern descent, he was surely referring in part to the Dajani family.

Back in 1990, as the Intifada was gaining momentum, Yauch was in New York, and that Frontline demo tape was at the front of his mind.

“Yauch loved Frontline,” recalls Horovitz. “He would always want us to cover their songs.”

Eventually, Yauch got his wish. For their third studio album, 1992’s “Check Your Head,” the Beastie Boys did a take on Frontline’s “Feel Like A King,” which Dajani wrote. Mike D replaced the lyrics with those from Sly Stone’s “Time For Livin.’” This choice could have been its own subconscious tribute to Geeby, who pushed Frontline to do hardcore covers of funk songs like Jimmy Castor’s “It’s Just Begun.”

The Beastie Boys took “Feel Like A King” and turned it into “Time For Livin’.”

In a 2017 retrospective for FLOOD Magazine, Marty Garner wrote that “Check Your Head” invented the Beastie Boys. The album went double-platinum, and “Time For Livin’” — a song that connected them to their punk roots — wouldn’t simply serve as one of the album’s deep cuts; it was a song the band made a music video for and performed on MTV.

While Yauch was campaigning for the Beasties to cover Frontline, hip-hop had long since caught the 2 train from the Bronx to downtown and found the ears of the kids of the West Village.

“The second we heard rap music — and I mean the second — that’s all we could listen to,” Nadia says. “There was something very punk about rap.”

When Geeby returned from the Bad Brains tour, he teamed up with Ross and Gamble to form a production unit called Stimulated Dummies. They worked out of a studio called SD50 in the basement of, you guessed it, Westbeth.

In an interview with Freddy Alva, Ross says the studio “was about the size of two broom closets.”

“It was this crazy basement that we used to play hide-and-seek in,” remembers Horovitz. “It used to freak me out when I was a little kid.”

Stimulated Dummies were given their name by none other than hip-hop giant Busta Rhymes. Working at the dawn of hip-hop’s golden age, Stimulated Dummies produced for popular alt-rap artists like Brand Nubian, Del the Funky Homosapien, Leaders of the New School, 3rd Bass, D-Nice, and KMD (MF DOOM's former rap group.)

“I sort of fell off the hardcore scene and started making rap records and sampling and chopping up beats and stuff,” Horovitz says. “Then someone told me that Geeby had made some single that had just come out. I was like, “Wait a minute, he’s making rap records?!”

Though Stimulated Dummies received a gold plaque for producing the 3rd Bass single “Pop Goes The Weasel,” Ross remembers Geeby’s shining moment as a rap producer being his work on Brand Nubian’s “Step to the Rear.”

“Geeby did that largely on his own,” Ross says. “[Brand Nubian member] Grand Puba had picked another beat off a beat tape and we tracked it out, which was a laborious thing to do back in the day, and Puba showed up and was like, ‘Yo, I can’t fuck with this.’ I was like, ‘What?!’ But [Geeby] didn’t wanna waste the studio time or the opportunity, so he pulled out a box of disks and the first thing he played was the loop for “Step to the Rear.” Puba wrote to the loop, and then we just made the drums right there, and that became the song. [Geeby] basically did like ninety percent of the song.”

“Step to the Rear” would go on to become one of the most sampled songs of the era, most famously by Gang Starr on “Take It Personal,” where DJ Premier sampled Grand Puba’s lyrics for the song’s hook. Zhane, Wu-Tang Clan, Pete Rock & CL Smooth, Fu-Schnickens, and Redman also sampled “Step to the Rear.”

“It’s probably my favorite hip-hop record we ever made, largely because Geeby was adaptable and rolled with the punches,” Ross says. “I was all stressed out, and he was like, ‘Eh, I got this,’ and that’s how it came to be.”

Produced by Geeby, alongside his Stimulated Dummies crew: Dante Ross and John Gamble.

Stimulated Dummies split up in the mid-’90s, but Geeby’s influence stayed with Ross, who sampled “Step to the Rear” when he produced the Carlos Santana and Everlast collaboration, “Put Your Lights On,” which would ultimately earn him a Grammy.

Meanwhile, Geeby assumed a role as a community leader, opening a rec center at Westbeth, mentoring youth from Manhattan to Brooklyn, and coaching high school basketball. He even coached Horovitz and Yauch’s wives and their friends in basketball once a week.

“He’s always been more like a coach,” says Keene. “He just wanted to help people out.”

“He was very inclusionary in everything he did,” adds Ross. “To be honest, sometimes that put us at odds with each other, because there would be some times when I would say, ‘Nah, man, f--- all that,’ and he would be like, ‘Nah, we gotta.’ He wanted everyone to participate and have a good time.”

Just like Sheikh Ahmad, Geeby was a bridge builder and a peacemaker.

“A lot of times on tour Geeby would curb H.R.’s bullying,” remembers Jenifer. “H.R. had a lot of subliminal, bullying-type things that he either consciously or subconsciously used to try to do. Not your garden variety bullying, just little things, and Geeby always found a way to check him. Whereas everyone else wouldn’t want to say s---. It was his confidence. Like, ‘Yo, my man, come here. You want a slice of pizza? Stop actin’ like a f----in’ idiot and you’ll get a slice.’ But Geeby wasn’t a bully with it; he had his own special way.”

Geeby’s hero status followed him through the years and spilled out onto the basketball court, just as it had begun on the PS41 playground decades before.

“You know Snuffleupagus from Sesame Street?” Horovitz asks. “Geeby was like that. We used to have a basketball game every Tuesday for like 20 years, and Geeby would just show up outta nowhere and come to the basketball game like twice a year, and everybody would be like, ‘Oh s---! F---in’ Geeby’s here! This is so cool!’”

In the new millennium, Geeby and Keene broadcasted an online radio show called Forty Deuce on beloved East Village Radio. Geeby’s prominence as a radio host earned him a cameo role in the acclaimed, Kid Cudi-starring HBO show “How to Make It in America.”

All the while, Nadia’s acting aspirations led to an accomplished career. She found roles on hit TV shows like “Sex and the City” and “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” co-founded a nonprofit theater company called Malaparte, and, most importantly, played in Major League Baseball’s All-Star weekend Legends & Celebrity Game in 2002. As YouTube became part of our cultural zeitgeist, Nadia wound up hosting “Caught Off Base” and “On The Fly,” two web series dedicated to her other true love: baseball. “Caught Off Base” gave her the platform to interview all her favorite baseball players, including many Yankees. The theme music? Composed by her best friend Adam Horovitz. The logo? Made by Cey Adams. The motivation? Geeby Dajani.

“Every step of the way, Geeby told me, ‘You can do this,’” Nadia says.

One thing she was adamant about as her career took off was not hiding her Arab identity. “I never let them change my name,” says Nadia.

Nadia’s premonition on the rooftop of Danceteria all those years ago came true. Adams went on to become a renowned visual artist. Horovitz and Yauch, along with Michael Diamond, formed what would become the best-selling rap group of all time, and Scilken traveled with them on tour until his passing in 1991. Keene played trombone on Beastie Boys albums through the years, hosted over 500 episodes of Forty Deuce with Geeby, and now lives in Vermont with his family. Bad Brains were nominated for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and Jenifer credits Geeby as his biggest inspiration.

“People have said that I created music that inspired them in a positive way,” Jenifer says. “But Geeby inspired me to be who and what I am.”

“He was our f---ing hero,” adds Horovitz.

“He couldn’t walk downtown without people who had known him when they were teenagers coming up to him,” says Ross.

“Geeby’s the King of New York,” says Jenifer.

Sadly, Najeeb Dajani passed at the end of 2019 after a battle with Lou Gehrig's disease. Still, he lives on.

Najeeb “Geeby” Dajani, ME62, the first and last Palestinian pharaoh, who was exalted by Warriors, and led a diverse caravan of GO Clubbers and Frontliners and Beasties and Bad Brains and Stimulated Dummies and Forty Deucers. He settled disputes and carried the Dajani name such that all whom he met would associate the West Village with him.