How Drake subverted a century of Hollywood stereotyping with one bar of Arabic

Editor’s Note: As Palestinians, politicians tell us that we are an “invented people,” the news media either completely ignores or vilifies us, and Hollywood stereotypes us (as you’ll read below.) Psychologically, this treatment leaves us feeling starved for any kind of positive representation. Any time anyone relevant to pop culture acknowledges or affirms us, it’s like a fleeting rush of euphoria; our group chats light up, our Instagram stories align, we get to explain to our parents who Noname is, and for a few hours, we have a chance to push those negative images out of our brain.

I’ve had the chance to be around Drake on a few occasions, and I can confirm that I heard him sprinkling Arabic into his conversation as early as 2015. For him to speak Arabic as part of his guest verse on British rapper Headie One’s track, “Only You Freestyle,” and to link his Arabic rhyme with Palestine and Jamaica, is incredible. Because of the timing of this verse’s release — the year Drake broke the record for most Billboard Top 10 singles — it’s hard to overstate its impact. Whether he realized it or not, Drake is subverting over a century of Hollywood portrayals of Arabic as a language spoken only by fictional terrorists. Here to articulate the significance better than I could is Suhel Nafar, who works as part of Spotify’s international artist and industry partnerships team. Nafar originally published this essay on LinkedIn. — Sama’an

For decades the Arab culture, language, and people have been demonized, so hearing our rich language used in a verse by one of the biggest artists in the world is actually a bigger deal than what Drake, Oliver El-Khatib, and Noah "40" Shebib — the three founders of Toronto-based record label OVO Sound — probably envisioned while smoking hookah and writing the song. Drake, if you’re reading this, shukran habibi.

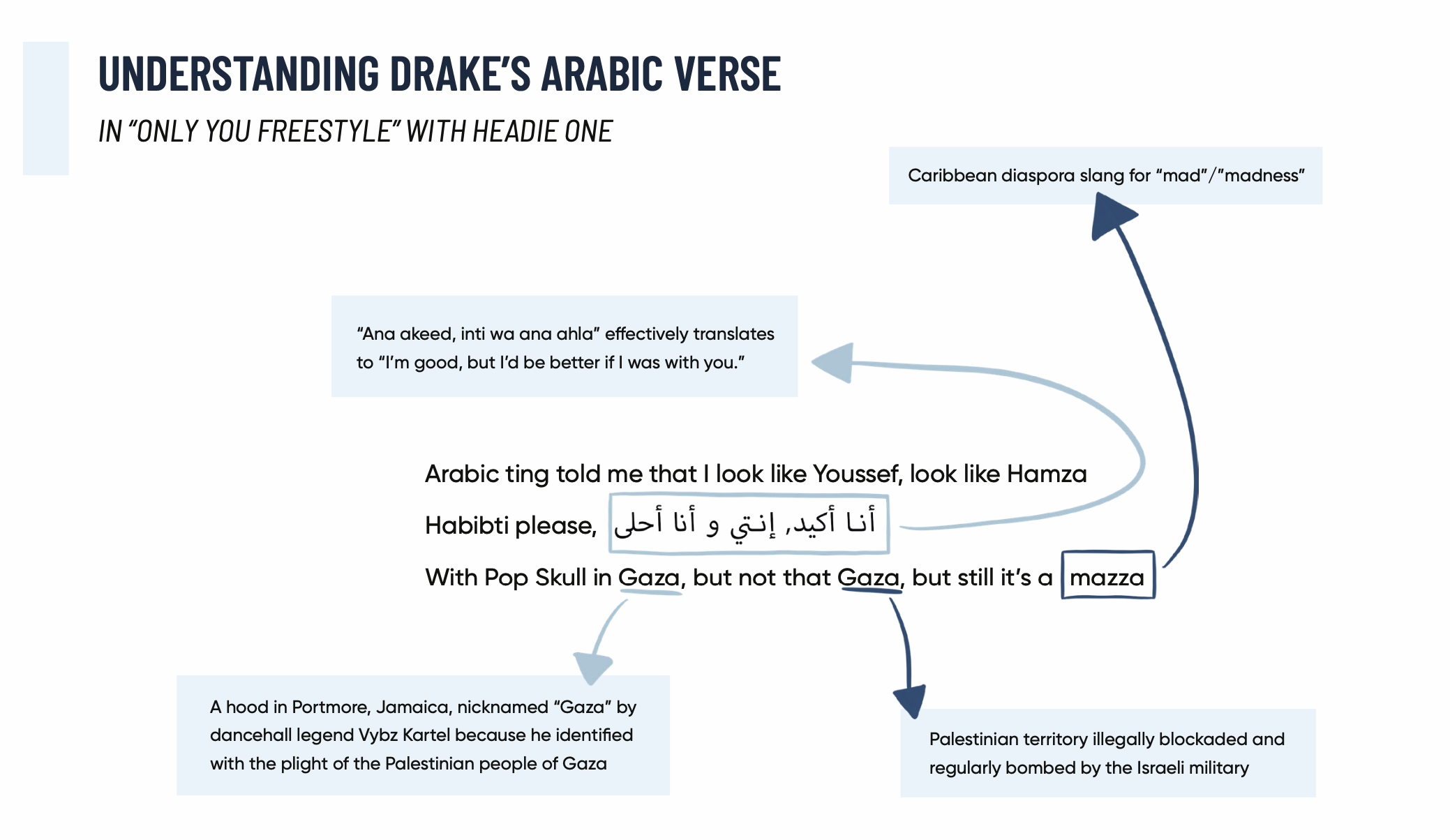

In his guest verse on Headie One’s “Only You Freestyle,” Drake raps, “Arabic ting told me that I look like Youssef, look like Hamza / Habibti please, ana akeed, inti wa ana ahla /With Pop Skull in Gaza, but not that Gaza, but still it's a mazza.”

For context on why I think this is a big deal, I turn to “Planet of the Arabs,” a 9-minute short film by Jackie Reem Salloum about Hollywood’s depiction of Arabs and Muslims. It is based on Jack Shaheen’s book, “Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People.” Shaheen studied 1,000 films produced between 1896-2000 with Arab and Muslim characters and found that:

12 films gave positive depictions

52 were neutral

Over 900 were negative

In the short film, Salloum masterfully and relentlessly edits a montage of these 900 negative depictions. This research by Shaheen, and its presentation by Salloum, are both important because they prove what Arabs have been complaining about for as long we’ve seen these images: that “terrorists” are very often cast as Arabs or people who look Arab. However these stereotypes are only a means to an end; dehumanizing people for decades through film and TV is a strong tactic used to gain public support to justify wars, invasions, and occupations.

I am a Palestinian who grew up under Israeli military control, which has been and still is erasing my culture and history in many ways. Being negatively represented in the media was and still is harmful to our psyche, and it plays a huge role in how we are treated. Art is how we push back against this harm, and there was a specific kind of art that really helped me when I was growing up: hip-hop. It completely changed my life. The younger me would have freaked out hearing Drake rap those Arabic bars; I would have felt lifted as much as I was when 2pac rapped, "I see no changes — can't a brother get a little peace? It's war on the streets and the war in the Middle East." While listening to the lyrics of artists like 2Pac, Public Enemy, and others, I learned about the struggle of being Black in America. I connected with what they said was happening on their streets because it was similar to the streets in the town where I grew up. This new perspective gave me the confidence to talk about our situation in Palestine through music, art, and culture. Because there have been more people of color writing, directing, and producing in Hollywood in the last 10 years, I’m glad to be able to say there have been more positive portrayals of us in film and media. Still, there needs to be more.

Anyone interested in a podcast going deeper into this topic can check out the three “Citations Needed” episodes titled “Hollywood & Anti-Muslim Racism.”