“Socialist” is Not a Four-Letter Word: The (Potential) Advantage of Bernie Sanders’ Alternative Agenda

As Bernie Sanders’ campaign gathered escalating momentum, it was unsurprising to see the establishment wing of the Democratic Party begin its offensive, with Elizabeth Warren initially indicating she might push forward all the way to the Milwaukee summer convention and Amy Klobuchar, Pete Buttigieg and Beto O’ Rourke dropping out of the running and giving Joe Biden their endorsement. During an interview with Anderson Cooper in the midst of Super Tuesday, Biden had this to say regarding the viability of Sanders’ candidacy: “I don’t think people are looking for revolution, I think they want results. And I think I’ve been able to make the case—I’ve been able to make it in South Carolina, and hopefully beyond—that I can produce results. And uh, the revolution he’s talking about is uh, you know, spending sixty billion dollars that I dunno where he gets the money…”

Biden no doubt has reason to be confident. He enjoyed a massive victory in South Carolina, and moderates are currently flocking towards him. These two details were powerful indicators that a standoff between Joe Biden and the self-proclaimed Democratic Socialist will be one of the most defining spectacles of this political moment, an outcome that the results of Super Tuesday ultimately confirmed, with Biden currently enjoying a statistical advantage over Sanders. And, unfortunately for Bernie Sanders, these developments mean that he and the rest of his campaign team will need to be doubly-prepared to fend off attacks from both the GOP and the corporate Democratic core about how his platform is “unrealistic,” “impractical,” or how it’s coming at “the wrong time.” Billionaire Mike Bloomberg opined that there could be no surer way to hand Trump the presidency a second time than continuing to humor Sanders’ points: “I can’t think of a way that would make it easier for Donald Trump to get reelected than listening to this conversation [with Sanders]. It’s ridiculous. We’re not going to throw out capitalism.” (As of Super Tuesday, Bloomberg has also dropped out of the running, and very quickly pivoted to endorse Biden; as several other commentators have pointed out, the agility of both actions should make the party’s larger designs and interests patently obvious).

Biden’s and Bloomberg’s comments are up to date, and yet they also exhibit an aged familiarity, reminiscent as they are of the 2016 Democratic party “strategy” of backing Hillary Clinton. At the time, that strategy might have been best summarized by the following three words: anybody but Trump. That is, establishment Democrats arrogantly rushed into the proceedings assuming that it didn’t matter who they brought forward, because Trump would never beat their candidate.

The rest, as they say, is history.

It would have been possible to write 2016 off as an error if it weren’t for the fact that some of the same dynamics are now repeating themselves. Only now, as Sanders’ campaign manager, Faiz Shakir puts it, with the Democratic party shoring up their ranks in this fashion, “The establishment has made their choice: Anybody but Bernie Sanders.”

And there is a very important reason for this. As a memo co-authored by Shakir and Jeff Weaver explains, “the choice between these two candidates… is a choice between the party’s core economic and social justice agenda, and the Washington establishment’s agenda that aims to protect and enrich the wealthy and well-connected.” The most privileged factions of the Democratic party fear Sanders more than Trump. In fact, Trump provides them with a strategic advantage: he is the boogeyman against whom they can continue to foment cosmetic outrage while never working at the root causes of what drives so much of the structural suffering and dispossession inherent to this country.

Sanders, on the other hand, calls attention to some of the root causes of oppression. Notice how I said calls attention to. This is not an accidental choice of words. As I’ll explain in more detail further below, the strength of the Sanders campaign is not in Sanders as a figure or potential candidate, or even his own avowed policies so much as the political momentum his campaign creates around issues that would otherwise be completely swept under the rug. Unequal access to health care. Gaping chasms separating the super-rich and the impoverished. An unjustly cost for education, with predatory interest rates for loans. And so much more. Sure, these types of issues would need accurate planning in order to be substantively countered, but there is also a point at which flimsy appeals to “be realistic!” are just not-so-subtly disguised defenses of the status quo.

And the status quo is precisely what is not working.

Just what kind of “results” can Biden claim to deliver when, by his own admission, they will essentially just be more of the same? The answer: none—and that’s precisely the point.

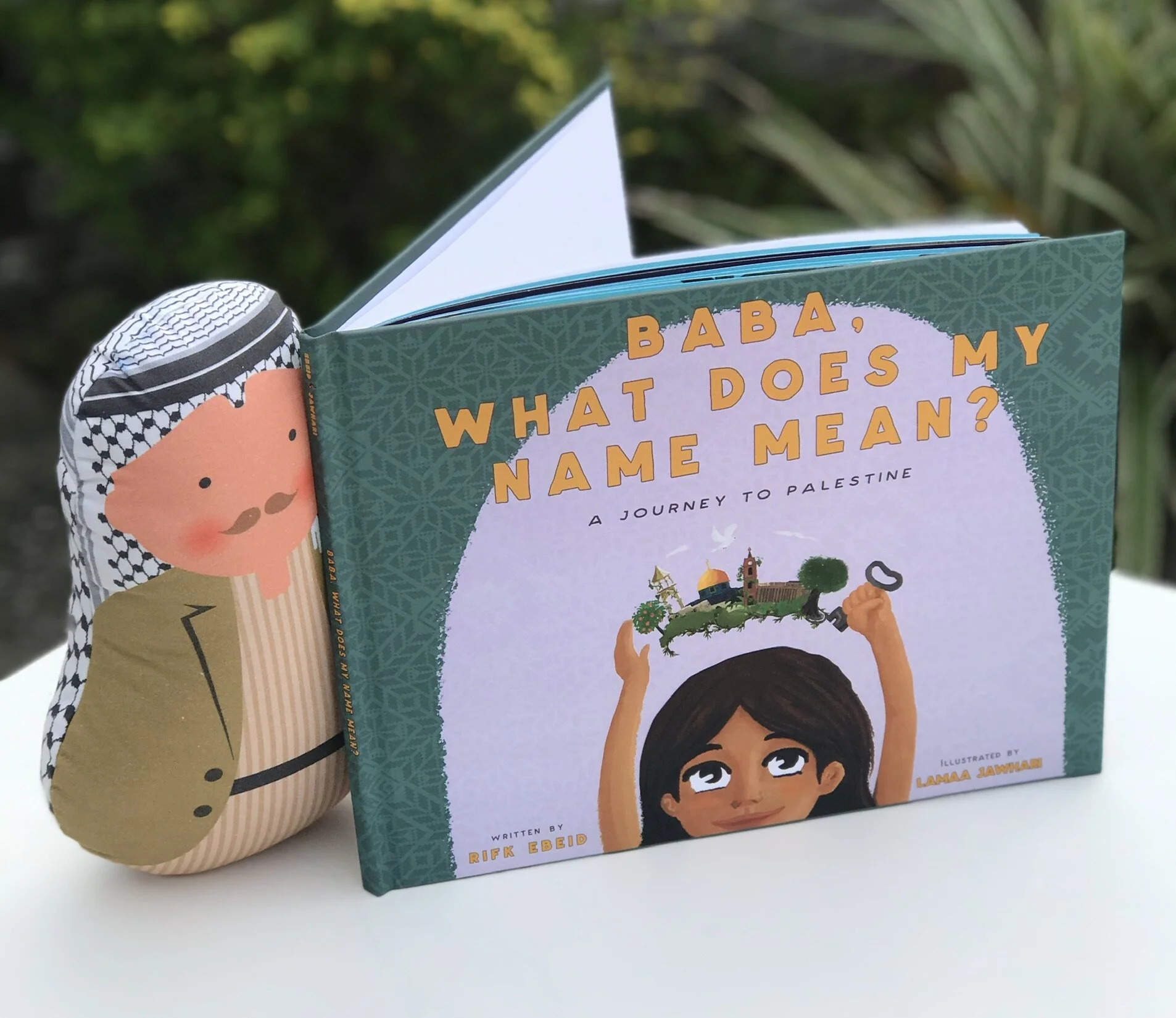

Palestine

It is a strange gift indeed to be a Palestinian taking note of the developments of any major political election in the US. For as long as I remember, this usually meant it was a given that Palestine and the suffering of the Palestinians would surely be ignored, and if Palestine was invoked, it would inevitably be as a synecdoche for Arab and “Muslim” barbarity; that’s how entrenched anti-Arab racism and Islamophobia are within the American imaginary. And the silence about the Palestinian struggle effectively made Palestinians into real-life referents for the shackled and deprived child of Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas”—it was simply a given that Palestinian suffering would continue to go unacknowledged while simultaneously powering the refinement of some of the most lethal innovations in military grade weaponry, racialized policing, surveillance, biometric monitoring, and crowd control tactics.

But the past few years have seen some unprecedented shifts in mainstream politics, with Rep. Betty McCollum (D-Minn.) calling Israel an apartheid state and introducing HR 4391 into Congress, a piece of legislation that would prohibit US aid from being used in the incarceration and torture of Palestinian children in contradistinction to International Law; Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) very publicly critiquing the influence of the Israel lobby; Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) initially speaking out about Israeli “massacre” and “occupation” (though, to be fair, she later backtracked on these comments somewhat), and Rep. Rashida Tlaib’s (D-MI) eventual refusal of the state of Israel’s “permission” for a planned congressional trip to the West Bank on the condition that neither promote nor engage in BDS.

And, of course, there is Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who is the first major presidential candidate to say he would cut aid to Israel for human rights abuses and has repeatedly spoken up for the Palestinian struggle during nationally televised debates. It is for these declarations, in addition to his decision to boycott the AIPAC conference this year, that a collective of Palestinian American individuals and organizations recently gave Sanders their endorsement.

Steven Salaita is right to note that Sanders’ actual record on supporting Palestinian rights is shakier than his current reputation suggests, and that it has by and large been his supporters who embrace the cause with more consistency, clarity, and principle. But to me this represents an opportunity, and the larger potential of Sanders’ campaign. In 2015, Black Lives Matter (BLM) protestors powerfully interrupted a Sanders rally. At the time, I was dismayed to see much of the backlash, which focused heavily on why BLM had targeted the “wrong” candidate. In fact, Sanders was the perfect candidate for such a visible demonstration, precisely because he was campaigning then (as he continues to campaign now) on a platform that is allegedly far to the left of any of his coevals in the Democratic party. Who but the (supposedly) farthest left candidate should be asked to account for how he intends to address racialized policing, brutality and incarceration? Sanders’ campaign subsequently took on a racial justice platform, but the efficacy or comprehensiveness of a subsequent amendment isn’t the point. Radical action and agitation can’t be reduced to the machinery of electoral politics, and that’s its strength—it can keep those who campaign on issues and causes for which our communities and fellow organizers struggle for day in and day out accountable to what they preach. And if Sanders’ campaign continues to take its cues from activists and others struggling on the ground—and does so explicitly, and without defensiveness—it would become an even greater force to be reckoned with, one that could attend to a whole range of issues in hitherto unprecedented ways and bring an even further slew of previously sidelined issues and questions into the day to day conversations of the political mainstream. Mainstream visibility is not salvation or liberation, and hypervisibility for a cause does not entail a total or even partial solution—sometimes it just means that the struggle continues unabated while simultaneously enjoying fifteen minutes of lip service. These are important considerations with which to grapple. But we can also reconsider just what “engagement” in a campaign means and looks like, and how important openings are seized upon in as creative, diverse and dynamic a manner as possible.

Here’s the thing: there are many who attribute Trump’s success to his performance of a kind of “outsider” political theater. He represents (even if he doesn’t ultimately embody) a fringe, anti-establishment character for many conservative, reactionary, and establishment forces alike. When conventions are failing (or perhaps, working too well), individuals will turn to the campaign that seems to be their greatest antithesis. By those standards, if the Democratic party were really interested in countering Trumpism, its strategy cannot be to be as unremarkable as possible. Has the Democratic party really become so ossified that it’s come to the point where its preferred candidate’s campaign can run on nothing but being a “nice guy?” In contrast to Bloomberg’s rebuttal, this approach, rather than launching a campaign that invites a reconsideration of some of the most oppressive systems and structures in American society, seems more of a guarantor of another four years of Trump. And if you have your doubts on this, I have a little exercise for you: put an apple in front of you, and ask yourself, seriously, how it compares and contrasts with Joe Biden.

Some important similarities will emerge. For one thing, neither Biden nor the apple are Donald Trump. Neither Biden nor the apple will give you a straight answer about their larger agendas. But the apple has one advantage: after the unsatisfying interview, it, unlike Biden, has a direct means of providing you with material sustenance.

Of course, the Democratic Party doesn’t really want change. It wants more of the same, and it’s made this amply clear by prioritizing its monopoly on establishment candidates and interests over a genuine attention to the need for real, viable reconsideration, even of many of the conventions it once took for granted whose oppressive blatancy to the general public has grown undeniable. Rather than accede to this, it continues attacking some of its more dynamic representatives leading the way in socio-political foresight like some kind of paranoid ouroboros.

But that’s ok. No politician will save us. We will need to do that for ourselves. As paradoxical as it may sound, to me, that reminder was one of the most important insights to come out of the Bernie Sanders campaign. The point isn’t whether Bernie wins or loses. The point isn’t what the polls grant, or withhold. It’s not buying into the logic of the “lesser of two evils.” Rather, it’s considering how best we can take advantage of the momentum that this campaign and attendant conversations have unleashed into the mainstream—how, for instance, those interested in veritable change can grapple with the fact that, due to the effort of Sanders and like-minded coevals, “socialism” is currently less stigmatized than it has been in preceding decades, with individuals from various generations coming to redefine what the term means to them. How can this energy be optimally utilized so as to help people agitate, organize, demonstrate, and engage in civic action in local and national contexts that continue to advance anti-oppressive agendas in an immediate and collective sense?

It’s not the campaign, it’s the momentum, a momentum whose irreducibility is one of its key strengths. Let’s keep it going. Let’s see how far we can take it. And most importantly, let’s see how far it will take us.